writes

Neither Fluffy nor Emasculated

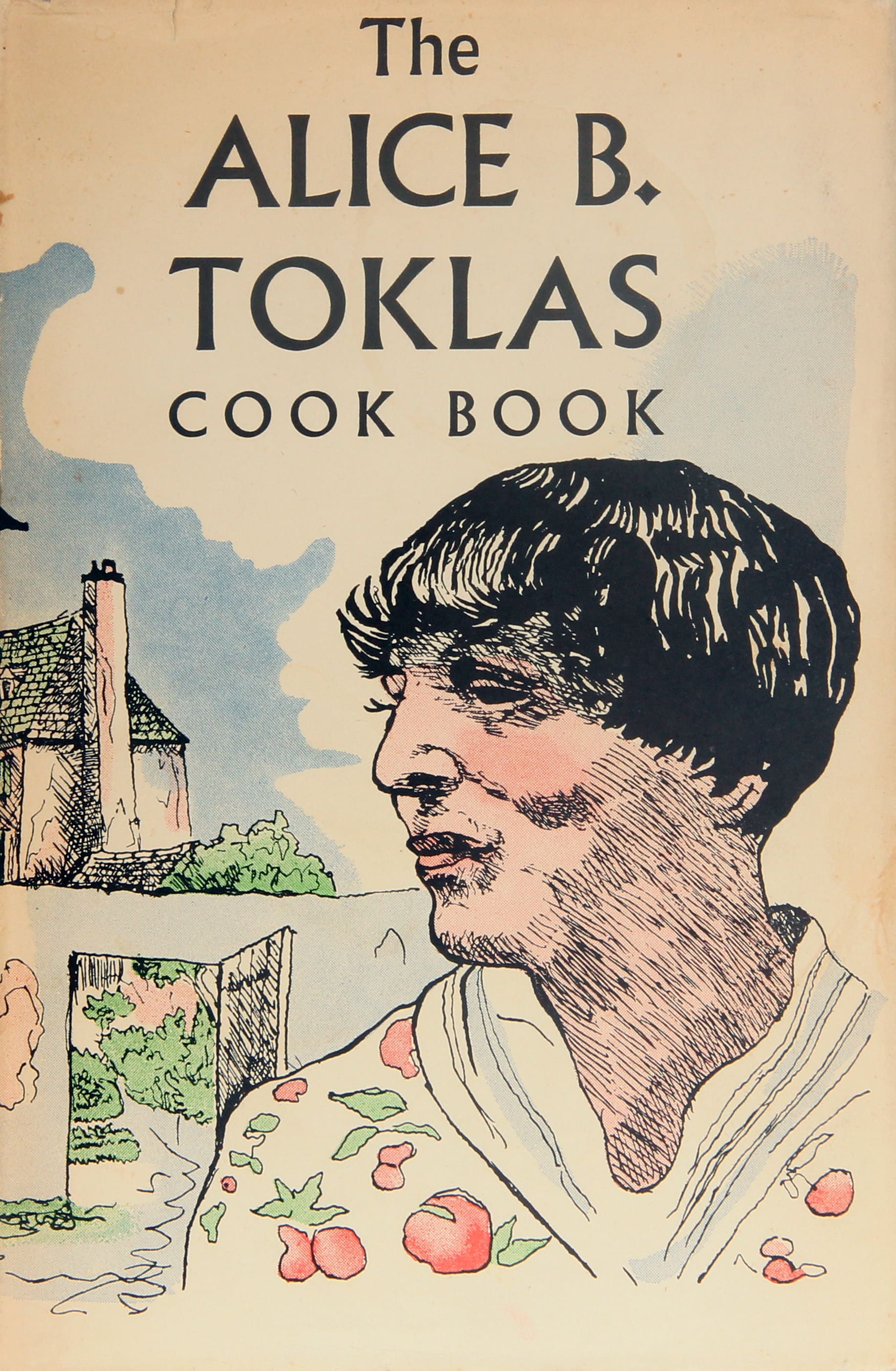

“Of course it takes much more than a lengthy attack of jaundice to make a decent cookbook, much less a minor masterpiece...” Quips M.F.K Fisher in her introduction to The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book.

And how true it is. It is widely known that Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas were an item. Much less known (and more fun to discuss in my opinion) is the fact that in 1954, after Gertrude’s passing, Alice published a cookbook that is one-part recipe, one-part autobiography. Alice had an unfortunate bout of events wherein her lover died and she soon thereafter became stricken with jaundice. In her time recovering she managed to write up the culinary stories of life with Gertrude while splicing her collection of recipes in between those memoirs. Alice openly narrates what it was like to cook, eat and travel with her partner. It is not the kind of cook book a woman of that time was writing. In the same year that Alice published her book, cook book readers at large also received the gifts of Betty Crocker’s Good and Easy Cook Book, and Wick and Lick: A Gazette of Chafing Dish Specialties into their libraries.

Alice was not the housewife that cooked aspics and meatloaves along with Betty Crocker’s instructions. She lived in France with Gertrude and cooked for their friends like Picasso and Thornton Wilder. Alice had a culinary craft all her own. The recipes she shares in her book are curated to her own interests – not to the interests per se of the men around her. Mushroom Sandwiches︎︎︎ were her specialty – they were an amalgamation of mushrooms with loads of butter, lemon juice, a pinch of cayenne, salt and pepper on toasted bread. Or in her adaptation of this first recipe she made them by scrambling eggs with parmesan into the buttery mushroom mixture and then serving them on toasty bread. These were brought on picnics with Gertrude. During WWII she saved up candied orange and lemon peel, pineapple, cherries, and raisins in glass jars. She saw them as symbols of hope for the day she could finally savor them. She made her Liberation Fruit Cake the moment the war ended.

But the book isn’t necessarily about a woman’s creative place in the kitchen either, at least not explicitly. Women are a strange topic in the book; they pop in and out as either worthy competitors or beings with no taste for food whatsoever. At one point Alice and Gertrude, while on their trip around the United States between 1934 and 1935, eat in a café in Columbus, Ohio. This café does not only have an all female staff but is managed and owned by women. Alice loves the food. “The cooking was beyond compare, neither fluffy nor emasculated, as women’s cooking can be, but succulent and savory.” Aside from the exciting fact that there was a female run business thriving in Ohio in the 1930’s, Alice gives the female chefs a heavy back-handed slap of a compliment. While these women managed to make something “succulent” and “savory,” she likens the cooking of most women to a cotton ball. She bashes the cooking skills of any women who might be reading her cook book. The tough part about reading Alice’s opinion of women’s cooking in the 1930’s is that it was probably true. The culture of women being at the helm of the kitchen, making food that the world travels to eat is stylish now. We see women chefs getting their own cooking shows, having full page spreads in newspapers, and even having magazines dedicated to them. But Alice lived in a time where women, for one did not look like her, talk like her, write like her, or cook like her. You could not find women in the food world of the 1950’s (other than the aforementioned Betty Crocker) without a magnifying glass.

Alice handles that magnifying glass well. There are special mentions of the kinds of female food connoisseurs that we look up to today in her cook book. The second chapter of the book, “Food in French Homes,” introduces the notion that French women “are not supposed to be gourmets.” But then:

There are of course exceptional cases, like that of a daughter who, instead of son, inherited her father’s famous wine cellar. At her table the maître d'hôtel presents each dish for this lady’s inspection before serving it to the guests... She has needed no man’s criticism to keep her culinary taste up to an almost solitary peak.

Alice handles that magnifying glass well. There are special mentions of the kinds of female food connoisseurs that we look up to today in her cook book. The second chapter of the book, “Food in French Homes,” introduces the notion that French women “are not supposed to be gourmets.” But then:

There are of course exceptional cases, like that of a daughter who, instead of son, inherited her father’s famous wine cellar. At her table the maître d'hôtel presents each dish for this lady’s inspection before serving it to the guests... She has needed no man’s criticism to keep her culinary taste up to an almost solitary peak.

Alice is in reverie of this woman’s independent taste buds. She makes note that no man’s opinion was obligatory in this woman’s tasting experience. There is also Alice and Gertrude’s cook Hélène who “was that rare thing, an invariable cook.” But apparently Alice “learned nothing about cooking” from Hélène, which is proved false by the paragraphs that come about Hélène’s cooking. “A lady did not cook,” according to Hélène. But she was a lady, cooking! Hélène had such refined cooking and hosting capabilities that she knew the nuances of celebrating or offending a guest through her food: “If you wished to honour a guest you offered him an omelette soufflé with an elaborate sauce, if you were indifferent to this an omelette with mushroom or fines herbes, but if you wished to be insulting you made fried eggs.” In the chapter “Beautiful Soup,” all about gazpacho, Alice references the opinion of Señora Marta Brunet – “a distinguished Chilean writer” on the beautiful soup. According to Señora Brunet, gazpacho is a meal of muleteers. These men brought the tomatoes, cucumbers, garlic, olive oil, dry bead and an earthenware dish with them on their trips. The ingredients were ground together and layered in the dish, closed tightly with a damp cloth and sat in the sun to cook. If the cloth was dry, it was time to eat. One wonders how Marta Brunet was privy to such knowledge as a woman? In a recipe for “Bass for Picasso,” Alice cites her grandmother’s method for cooking the fish. Her grandmother apparently “had no experience in cooking and... rarely saw the kitchen but... had endless theories about cooking...” Her theory was that “a fish having lived its life in water, once caught, should have no further contact with the element in which it had been born and raised.” Very conceptual for someone who didn’t cook. Madame Loubet was a “first-rate” cook in the French city of Mâcon whose cuisine was both “delicate and distinguished.” She made for Alice and Gertrude, a menu of asparagus tips with butter and cream, veal fricandeau with truffles as well an omelet with truffles and a fresh local cheese. According to Hélène’s omelet philosophy, Madame Loubet’s omelet was a high honor. Alice and Gertrude returned often to eat her food.

Since the book is a cookbook – an inherently feminine form – it lends itself beautifully as a platform for introducing powerful lady cooks to the world of 1950’s readers. Alice’s own distinctive queer female perspective looks at the female culinary figures with the respect they’ve always deserved. Just the simple fact that she wrote about them, remembered them, and in some cases, shared their recipes, shows the true impression their talents made on her. I will be making omelets for my next guests.

Since the book is a cookbook – an inherently feminine form – it lends itself beautifully as a platform for introducing powerful lady cooks to the world of 1950’s readers. Alice’s own distinctive queer female perspective looks at the female culinary figures with the respect they’ve always deserved. Just the simple fact that she wrote about them, remembered them, and in some cases, shared their recipes, shows the true impression their talents made on her. I will be making omelets for my next guests.